The Tower of Babel

A Deity's Response to Human Aspiration

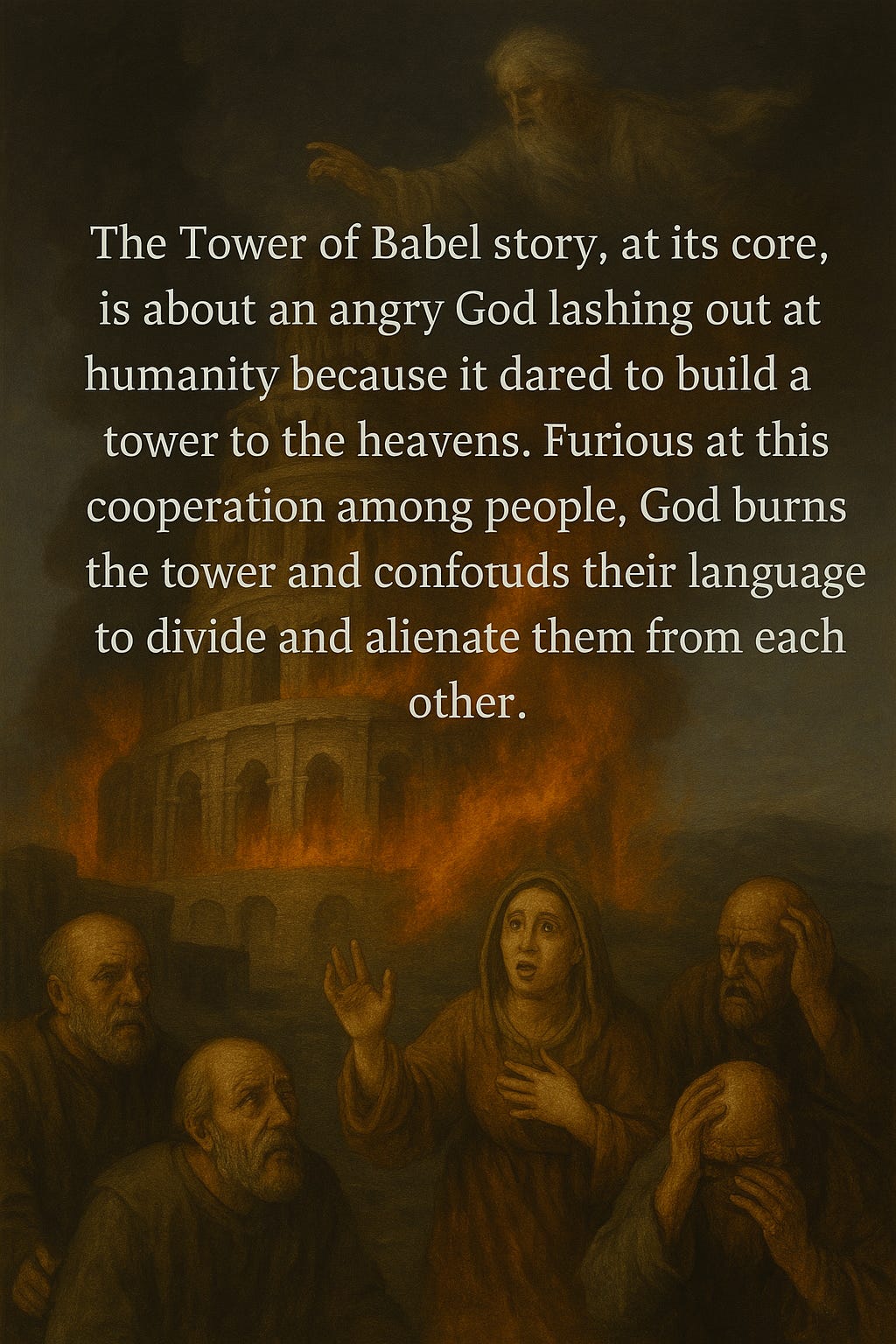

Much like the story of Noah’s Ark, the Tower of Babel is often presented as a tale of divine wisdom intervening in human arrogance. In Genesis 11:1–9, humankind—united by one language and a shared purpose—gathers on the plains of Shinar to build a city and a tower “with its top in the heavens.” But rather than allow this collective ambition to flourish, God descends, confounds their language, and scatters them across the earth. This brief narrative is typically interpreted as a cautionary tale about pride and the limits of human ambition. But under closer scrutiny, it reveals a troubling vision of divinity—one in which unity, progress, and cooperation are punished, not celebrated.

The Tower of Babel is not a story of judgment on evil; it is a story of punishment for potential.

There is no indication in the text that the builders of the tower are violent, cruel, or corrupt. They are not waging war or defying moral laws. They are working together—peacefully and with purpose. Their “sin” is that they seek to “make a name” for themselves and avoid being scattered. In other words, they seek community, achievement, and perhaps even transcendence. In this light, the Tower of Babel becomes a profound example of divine insecurity—a god who reacts not out of justice, but out of fear that humanity might grow too strong, too united, too capable.

What kind of deity disrupts such cooperation?

The punishment—linguistic division and global dispersal—can be interpreted as a theological justification for the fracturing of human civilization. Instead of affirming the beauty of human unity and shared vision, the God of this story imposes confusion and chaos. In the wake of Babel, humanity is condemned to misunderstanding, miscommunication, and isolation. If taken as literal history, the story is a divine act of sabotage. If taken as allegory, it encodes a worldview in which centralized power and collective identity are threats to be eliminated.

This raises deeply unsettling implications. In both Babel and the Flood, we see a God who intervenes to halt human development. In the Flood, it is through destruction. In Babel, it is through division. In both, the deity enforces a limit not on evil, but on aspiration. The divine message is clear: you may live—but not dream too big. You may strive—but not succeed beyond the parameters I define.

This is not the vision of a benevolent creator guiding humanity to enlightenment. It is the vision of a jealous god who fears rivals, even among his own creations.

There is something tragic about the Tower of Babel. It is a rare moment in Genesis where humanity is not depicted as fallen or wicked but as imaginative, industrious, and unified. And yet, even this brief utopia is stamped out—not by sin, but by divine decree.

In a modern context, the Babel story has been used to explain the origin of different languages and cultures. But the moral framework it offers is chilling: diversity born not of organic evolution, but of punishment; culture as consequence, not celebration.

We must ask what such stories do to our collective conscience. What values do they promote? What gods do they teach us to fear—or to worship?

If the Flood story reveals a God who obliterates life to restart creation, then Babel reveals a God who fragments life to limit its power. In both cases, it is not human depravity that offends the divine—it is human possibility.

As with Noah’s Ark, the story of Babel must be reckoned with honestly. To revere these acts without critique is to endorse the suppression of human potential in the name of divine order. But if we dare to read these stories with clear eyes, we might recover what was lost at Babel: the right to reach for the heavens together.