Watching The Sopranos for the first time, long after its original air date, is a strangely immersive experience. The series, so highly lauded in television history, strikes a curious balance between fascination and revulsion, pulling me into a world that, at times, feels grotesque in its ethics and allure. The characters, particularly Tony Soprano, oscillate between deeply repellent and oddly compelling, forcing me to question the contradictions inherent in their lives and, by extension, my own reactions to them.

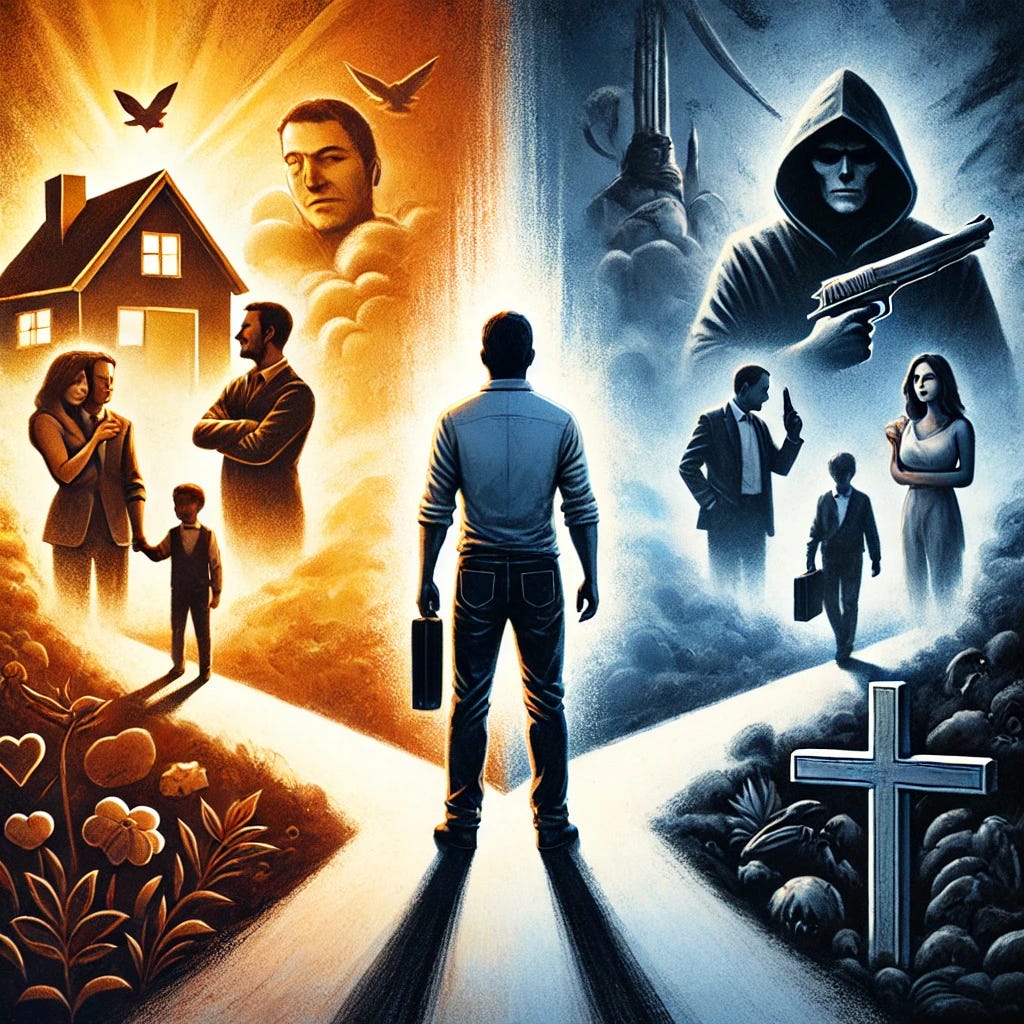

Tony Soprano embodies a type of American anti-hero we’ve come to both detest and admire in modern entertainment. He is violent, morally bankrupt, and entangled in a web of deception that sustains his power. Yet, it’s impossible not to feel a tug of intrigue—perhaps even empathy—as we watch him navigate his personal struggles, particularly his therapy sessions that reveal a man torn between the traditional expectations of his criminal world and the vulnerabilities of his mind. Despite this internal conflict, I find myself deeply repulsed by Tony’s ability to rationalize brutality, even as I recognize the very real psychological complexity the show offers. In many ways, The Sopranos forces us to confront how easily we become absorbed by the very people whose values we reject.

But it’s not just Tony. Carmela, Tony’s wife, is equally perplexing. She seems the archetype of the doting wife, yet she is so much more. Her allure—both physical and emotional—is undeniable, and I can’t help but feel drawn to her strength and resilience. There’s a powerful sensuality in her suppressed desire, in her moments of vulnerability with other men, which makes her character all the more intriguing. But here’s the rub: how much of her torment is truly earned? Carmela knew the life she was entering. She understands the world her husband inhabits, the moral compromises that come with it, and yet she clings to her Catholicism as though it might redeem her. It’s difficult to reconcile her awareness with her suffering. Is she really tortured, or is her inner conflict part of the very fabric of this dark, symbiotic relationship?

What I find particularly disorienting is the romanticism in this portrayal of the mafia family. From Mario Puzo’s Godfather to The Sopranos, there is a persistent admiration for the family-centric ethos of organized crime. Even though these families operate in a brutal, criminal underworld, they are depicted with an unspoken code of honor—a loyalty that stands above all else. It’s as though the very structure of family, with its intricate loyalties and betrayals, is glorified. This romanticism is especially perplexing when we consider how we, as viewers, are invited to appreciate the ‘nobility’ of mafia killers, or at least the bonds that tie them together. Why do these characters—murderers, thieves, and extortionists—get to be figures of admiration?

In part, I suspect it’s because the mafia, at its core, reflects a deep-seated cultural appreciation for familial loyalty, one that extends into the fabric of the Italian Catholic identity. This ideal of "family first" reverberates in ways that can often make us overlook the moral transgressions of these characters, allowing their commitment to family to justify their crimes, or at least make them palatable. Yet, as I watch The Sopranos in 2024, I can’t help but see how warped this cultural depiction feels. It’s almost as though we’ve collectively accepted, through years of media conditioning, that this twisted loyalty to family makes the mafia lifestyle less egregious, even honorable.

In particular, the portrayal of Catholicism in this series feels emblematic of a broader issue. Catholic guilt permeates the lives of these characters, offering them just enough of a moral compass to keep them grounded in their cultural identity but not enough to alter their behaviors. For Carmela, her faith is both her solace and her shackle. She is constantly trying to reconcile her moral convictions with her lived reality as the wife of a mafia boss. Yet, this depiction of Catholicism—of confessions and penance as moral absolution—feels hollow. The Catholic faith, as presented through this mafia lens, seems more like a crutch for characters than a path toward redemption. It’s a caricature of faith, reduced to a series of rituals devoid of real substance or transformation.

The shift in romanticism over the past 50 years is also worth noting. When The Godfather was released in the early 70s, there was still a reverence for this mafia lifestyle—a mystique about the organized crime family that captured the public imagination. The family enterprise, no matter how bloody, was romanticized as an extension of the American Dream, albeit with a dark twist. But watching The Sopranos now, in the context of our current cultural moment, feels different. The same romanticism is still present, but it’s overshadowed by a more pervasive sense of moral decay. The idea that we should admire these characters, or at least be seduced by their world, feels increasingly uncomfortable.

In the end, The Sopranos is a brilliant study in contradictions. It forces us to look closely at the intersections of power, loyalty, and morality, and how these dynamics play out within the framework of a criminal family. Yet, it also begs the question: why do we continue to romanticize these stories? Why do we, even now, find ourselves drawn to these characters who operate outside the bounds of society’s moral codes? Perhaps it is the allure of power and the intoxicating pull of family connections that make these stories so compelling. But as I continue watching The Sopranos, I find myself questioning not only the ethics of the characters but my own reaction to them. The romanticism of organized crime may have lost its sheen, but the fascination with the human drama behind it remains impossible to ignore.