Visiting the Dead Sea Scrolls exhibition at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley this week felt like stepping into the pages of history. It was a bucket list moment for me—a chance to see fragments of the very texts that have shaped so many conversations about religion, culture, and identity. Standing inches away from pieces of Paleo-Exodus, and Deuteronomy, as well as ossuaries intricately carved with ancient symbols, I felt the weight of the past pressing against the present. These weren’t just artifacts; they were echoes of lives, beliefs, and struggles long gone. Having read extensively about the Scrolls, including John Allegro’s provocative work The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, I felt a familiar sense of awe and skepticism. What are these scrolls really telling us? Who wrote them? And more intriguingly—why?

For decades, the Dead Sea Scrolls have been attributed to the Essenes, a Jewish sect supposedly living in the nearby Qumran community. This assumption, largely based on historical accounts from writers like Josephus, aligned neatly with the narrative that these texts were the religious writings of an isolated, ascetic group. But as I walked through the exhibit, it struck me how little we actually know. Scholars now debate this Essene hypothesis, suggesting that the Scrolls could have come from various Jewish groups in Jerusalem, hidden in the caves during the Roman siege to protect sacred writings. The diversity in handwriting, theological perspectives, and even linguistic style within the Scrolls challenges the idea of a single source. It’s possible that these scrolls represent a broader effort to establish religious and cultural claims during a time of chaos and displacement—a recurring theme in human history.

Take, for instance, the famed Rosetta Stone. While not a forgery, this monumental artifact was a tool of assertion. Inscribed with the same decree in three scripts—hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Greek—it was essentially a political document designed to solidify the authority of Ptolemy V over Egypt. By presenting his rule in the language of the priests (hieroglyphs), the common people (Demotic), and the administrators (Greek), Ptolemy was making a clear statement: this land, with its diverse cultures, belonged to him. The stone’s role as a unifying claim over a fractured society underscores how texts and artifacts can serve as tools of power.

But history is rife with outright forgeries as well. One notable example is the Kensington Runestone, a slab allegedly carved by Norse explorers in the 14th century and “discovered” in Minnesota in 1898. For decades, it was heralded as proof that Vikings reached the heart of North America long before Columbus. However, linguistic analysis and inconsistencies in the runic inscriptions eventually exposed the stone as a 19th-century hoax, likely created to bolster claims of Scandinavian heritage in the region. It’s a fascinating case of a forged artifact being used to assert cultural and, indirectly, territorial legitimacy—essentially rewriting history to fit a narrative.

So what if the Dead Sea Scrolls are another example of this phenomenon? What if they were intentionally hidden—or even created—to support a particular claim to land or identity? Ancient peoples were no strangers to such tactics. From the biblical conquest narratives to medieval charters, the use of texts and monuments as instruments of power and legitimacy is a thread that runs through human history.

Reflecting on this, my visit to the exhibition felt even more profound. These scrolls, whether genuine relics of a lost sect or tools of ancient propaganda, remind us of the enduring human desire to leave a mark, to tell a story that outlasts us, to assert ownership over a piece of the world. Whether their origins lie with the Essenes or another group altogether, their discovery—and the questions they raise—offers a mirror to our own modern struggles with identity, authenticity, and belonging. Standing in that room, surrounded by history, I felt a deep connection to the timeless dance of truth and fiction, belief and skepticism, that defines our shared past.

Fabricating the Past: How Forgeries Shape Land Claims

Throughout history, forgeries have been wielded as tools to rewrite narratives, shape cultural identities, and support territorial claims. These fabrications, often presented as legitimate artifacts or documents, have influenced historical discourse for decades before being exposed. Here are some compelling examples.

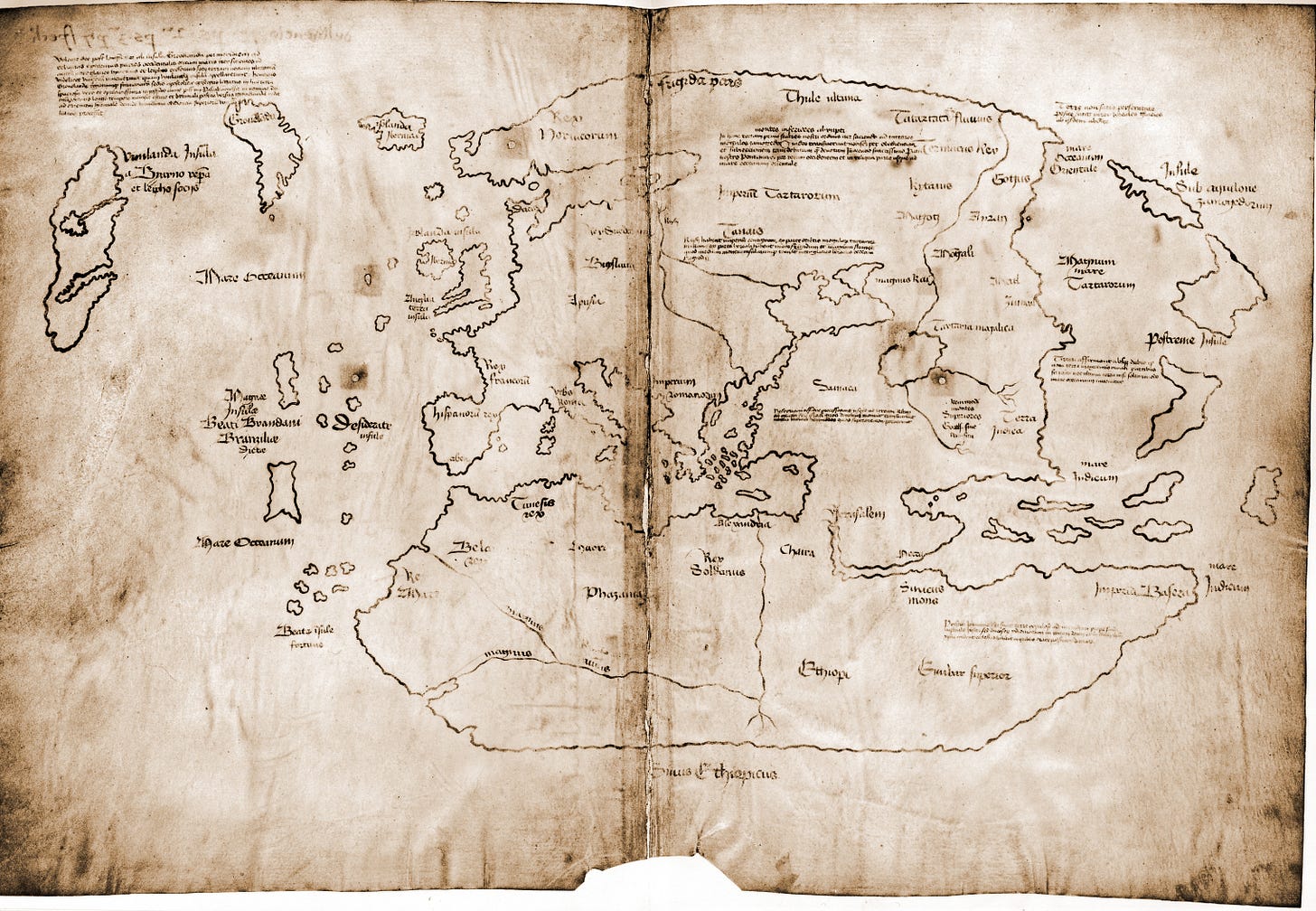

The Vinland Map

Discovered in the 1950s, the Vinland Map appeared to show Norse exploration of North America long before Columbus. This artifact seemed to validate sagas about Leif Erikson’s journey to "Vinland," suggesting that Norse explorers not only reached North America but also mapped it. Such a discovery bolstered Scandinavian heritage claims. However, later analysis revealed that the map was a 20th-century forgery, as its ink contained modern synthetic compounds. While a fraud, the map highlighted how artifacts can be crafted to assert cultural significance and territorial legitimacy.

The Calaveras Skull

In 1866, miners in California’s Calaveras County unearthed a human skull buried under volcanic rock, which was claimed to date back millions of years. At the time, the skull was hailed as evidence of an ancient human presence in North America, with some using it to support Native American claims to the land. However, further investigation revealed it to be a hoax, likely planted by miners to discredit scientific research. The skull, belonging to a more recent period, underscores how fraudulent artifacts can be leveraged to influence cultural and territorial narratives.

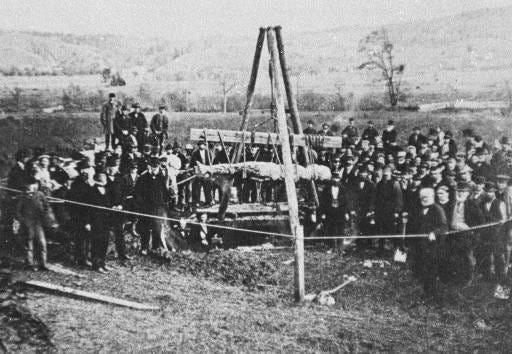

The Cardiff Giant

The Cardiff Giant was "discovered" in 1869 in Cardiff, New York—a massive stone figure resembling a human, believed by many to be a petrified man or evidence of a biblical race of giants. Promoters linked the artifact to religious texts, using it to support claims of divine ties to the land. Ultimately, the giant was revealed as a hoax orchestrated by George Hull, who had commissioned its creation and burial as a prank. Despite its fraudulent origins, the Cardiff Giant fueled debates about biblical history and the historical significance of the region.

The Glozel Tablets

In 1924, a French farmer uncovered clay tablets, bones, and pottery in the village of Glozel, France. Hailed as evidence of an ancient European civilization, the discovery sparked national pride and debates over France’s prehistoric heritage. Later investigations revealed the artifacts to be forgeries, likely crafted to gain fame or financial advantage. Nonetheless, the Glozel discovery highlights how easily fabricated artifacts can become rallying points for territorial and cultural claims.

These cases illustrate how forgeries—whether intentional or opportunistic—can wield immense power in shaping perceptions of history and legitimacy. They remind us that even the most compelling narratives must be critically examined, as the past is often more complex than it appears.