After 25 years of working in education—across multiple districts, county offices, and state-funded intervention teams—I had resigned myself to the idea that school reform was just an elaborate game of bureaucratic hot potato. Every district I worked with seemed fixated on systemic solutions—restructuring leadership, tweaking policies, rearranging funding streams—all while leaving the actual classroom experience untouched. Teachers were still handed new buzzwords instead of tangible support, and students faced the same challenges year after year, regardless of the latest district-wide initiative.

But now, for the first time in my career, I find myself at a school district that gets it. Instead of launching another top-down, multi-million-dollar transformation plan, the school district I currently work for focuses where it matters most: the classroom. The reforms happening here aren’t about administrative reorganization or governance shifts. They’re about real, practical, daily improvements in teaching and learning—the kind that directly affect students rather than just looking good in a strategic plan.

And it’s refreshing. It’s different. It makes me wonder: Why hasn’t this been the norm all along?

Because the truth is, for decades, we’ve been approaching education reform all wrong. We’ve been obsessed with fixing the system when what needs fixing is the way students experience learning. And that’s where the real conversation should begin.

Another Conference

I’m sitting at another school improvement conference, this time in Pasadena. If you’ve ever attended one of these, you know the drill: inspirational quotes, PowerPoint slides full of jargon, and a panel of superintendents saying, with great enthusiasm, things that could have been told 30 years ago.

And they were said 30 years ago.

A memory hits me: I’m a young teacher in Los Angeles Unified, sitting in a similar conference, listening to then-Superintendent Roy Romer wax poetic about bold new initiatives, data-driven decision-making, and the imminent transformation of public education. It sounded so promising—like a school version of “New Year, New Me.”

But here I am, hearing the same reform slogans with fresh coats of paint decades later. The achievement gap? Still there. Standardized test scores? Still stagnating. Bold new initiatives? It's more like reheated leftovers from the last education summit.

That’s when I realized that public education isn’t failing due to a lack of effort, intelligence, or innovation. It’s failing because, deep down, it’s not designed to succeed. It’s a political institution first and an educational one second—an elaborate bureaucratic Rube Goldberg machine that exists primarily to sustain itself.

So, should we even keep trying to fix it? Or are we just endlessly slapping duct tape on a sinking ship?

A Brief and Depressing History of Education Reform

Every generation thinks it’s about to crack the code on education reform.

In the 20th century, we had progressive education, STEM mania (thanks, Sputnik), and Brown v. Board of Education, which promised to dismantle systemic inequities. The 1983 report A Nation at Risk warned that our schools were one step away from educational armageddon. In response, we got No Child Left Behind, ironically leaving quite a few children behind.

Since then, we’ve cycled through charter schools, voucher programs, technology-driven learning, and whatever buzzword-filled initiative is in vogue this year. And yet, despite all the reforms, we still can’t seem to get most students proficient in reading and math. The achievement gap? Like a lousy houseguest, it refuses to leave.

It’s almost like we’re playing an endless game of educational Whac-A-Mole—every time we smack down one problem, another pops up, and the whole thing starts over.

Education: A Political Machine in a Cap and Gown

Let’s be honest: public schools are not nimble, innovative learning hubs. They’re bureaucratic fortresses, bogged down by layers of governance, regulations, and enough red tape to gift-wrap the moon.

Unlike businesses that innovate or go bankrupt, public schools don’t face existential threats. Whether they succeed or fail, they keep getting funded. They’re less like high-performance engines and more like a government-subsidized treadmill—lots of movement, no forward progress.

And then there’s the politics. Oh, the politics.

At the local level, school board elections tend to be won by whoever convinces a few hundred highly motivated voters (mostly retirees, local activists, and the one person who reads school board minutes for fun). This makes them prime targets for special interests, such as teachers' unions, real estate developers, and ideological groups looking to reshape curricula.

Meanwhile, at the state and federal levels, education policy is dictated less by research and more by political ideology. One administration advocates standardized testing, while the next advocates “teacher autonomy.” In the end, nobody wins—except the companies selling the tests and curriculum packages.

And let’s not forget how schools are funded—primarily through property taxes. Meaning? Wealthy neighborhoods get well-funded schools with brand-new MacBooks, and poor neighborhoods get overcrowded classrooms with 15-year-old textbooks that still list Pluto as a planet. Every attempt to fix this—whether through school finance reform, busing policies, or equity-based funding models—faces a level of resistance usually reserved for unpopular wars.

A System Designed for Dysfunction

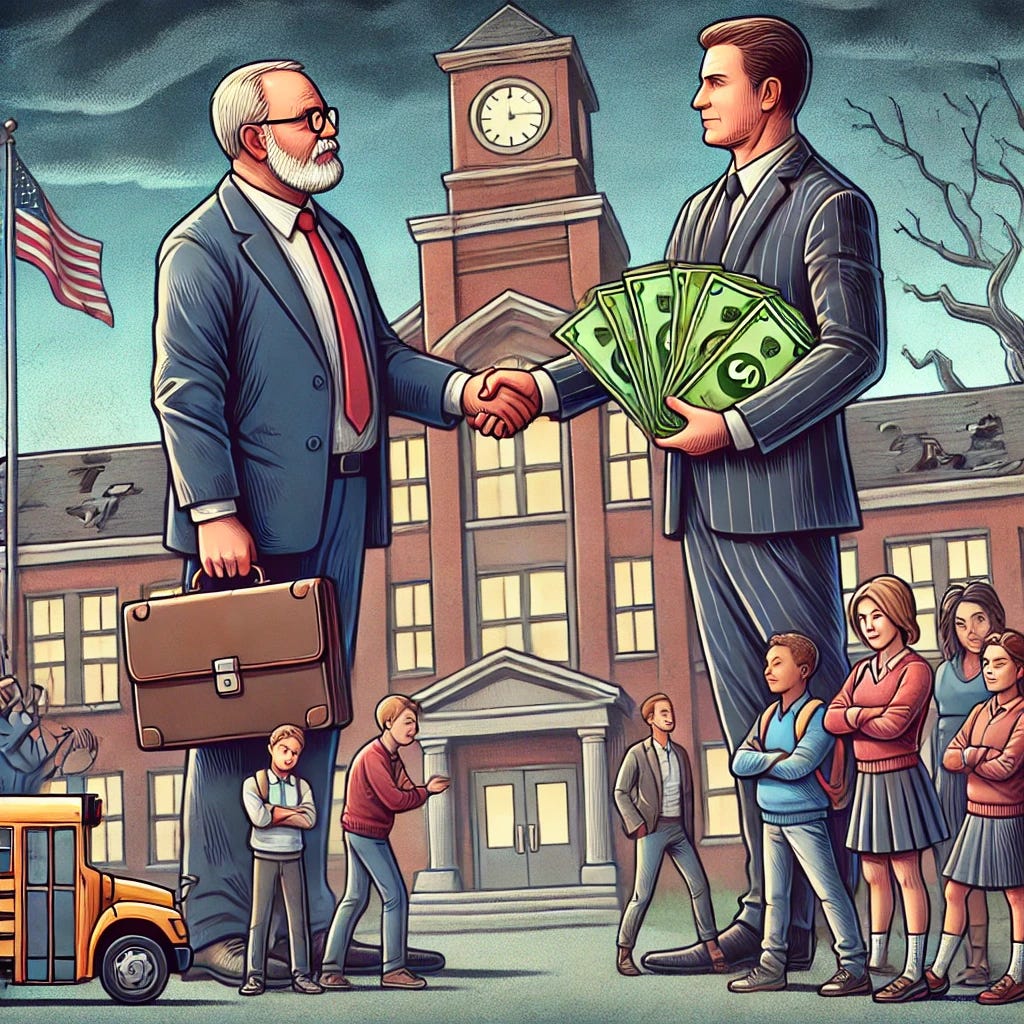

With billions of dollars flowing into school districts, it’s no surprise that education is a hotbed for mismanagement and corruption. Contracts for textbooks, technology, and infrastructure are lucrative, and school districts often spend ridiculous sums on things that don’t improve learning.

Take the standardized testing industry. Companies like Pearson and College Board have turned assessment into a multibillion-dollar empire despite mounting evidence that high-stakes testing does little to help kids learn.

And the revolving door of district leadership? It’s like a game of musical chairs but with six-figure salaries. Upper management comes in with big promises, implements half-baked reforms, and leaves before anyone can see whether their ideas work. Meanwhile, teachers are left with professional development sessions that tell them to “differentiate instruction” without giving them the resources or time to do so.

While essential in protecting educators, teacher unions can also be guilty of blocking necessary reforms, such as performance-based evaluations or tenure reform. And let’s not even get started on the textbook industry, where a handful of publishers have a stranglehold on what is taught in classrooms.

It’s a system where everyone benefits except the students.

Is There Hope? Maybe. Just Not Here.

The good news? Other countries have figured this out.

Finland treats teachers like doctors—highly trained, highly paid, and given autonomy in the classroom.

Singapore emphasizes mastery over rote testing, so students understand the material instead of cramming for exams.

Canada has a more centralized funding model, meaning students in wealthy and poor neighborhoods get roughly the same resources (what a concept!).

What do these countries have in common? They don’t let education get bogged down by the same level of political nonsense as the U.S. They don’t endlessly debate whether evolution should be taught or whether teachers are “indoctrinating” students. They… educate kids.

What Might Work

If we genuinely want to fix this mess, we need to stop pretending that minor tweaks will do the job. Here are a few radical-but-necessary changes:

Decentralize decision-making: Give schools and teachers more autonomy instead of complicating bureaucracy.

Fund schools equitably: Stop tying school budgets to local property taxes. A kid’s education shouldn’t depend on their ZIP code.

Reform teacher compensation: Pay teachers like professionals and introduce accountability measures that reward excellence instead of just seniority.

Ditch standardized testing: Use assessments that measure learning rather than test-taking ability.

Hold leadership accountable: District officials should be required to stay long enough to implement their reforms—or at least long enough for us to remember their names.

None of these are easy. But let’s be honest—what we’re doing now isn’t working either.

Conclusion: A Necessary Illusion

The truth is that K-12 education reform often feels like an elaborate illusion. We keep hoping that the next significant initiative will finally fix things, but the system is designed to keep itself alive, not to improve.

We must stop playing the game on its terms if we want real change. That means challenging entrenched power structures, rethinking how we fund schools, and learning from countries that get this right.

Otherwise, we’ll keep returning to conferences, listening to the same speeches, waiting for a change that isn’t coming.

And personally? I don’t have another 25 years to waste.

You?