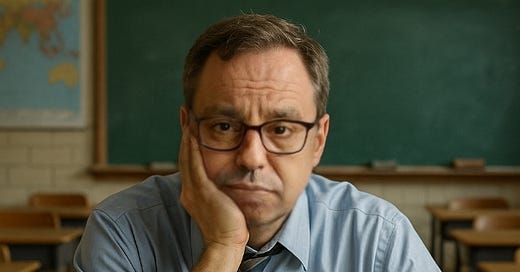

If you’ve ever sat through a professional development session where someone earnestly declared, “I’m an auditory learner,” as if it were their Hogwarts house, congratulations—you’ve witnessed one of education’s most persistent myths in action. The idea that students learn best when taught according to their preferred “learning style” (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, etc.) has become gospel in some schools, often laminated and hanging next to the fire exit. But here’s the kicker: despite its popularity, decades of research have shown that tailoring instruction to these so-called styles has little to no impact on actual learning outcomes. So why do we keep believing in it like it’s educational astrology? Let’s dig in.

The Origin Story

The idea of learning styles took off in the 1970s and 80s, just as the self-esteem industrial complex was hitting its prime. Psychologists and educators, with good intentions and possibly too much access to felt-tip markers, began promoting frameworks like VARK (Visual, Auditory, Reading/Writing, Kinesthetic). The idea was simple and intuitively appealing: if we teach students the way they like to learn, they’ll learn better.

Unfortunately, research consistently shows that this doesn’t hold up. A comprehensive review by Pashler et al. (2008) concluded that there is “no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning styles assessments into general educational practice.” Translation: there's no solid proof that matching teaching style to a student's preferred learning style improves outcomes. None. Nada. Not even a glimmer.

In fact, a 2015 study by Rogowsky et al. found that students performed equally well regardless of whether material was presented in their “preferred” learning style. What mattered more was the nature of the content and the quality of instruction, not the alleged sensory preference of the learner. Imagine that.

So Why Won’t This Myth Die?

Great question. Like a moth to a lava lamp, humans are drawn to tidy categories. Learning styles offer a sense of control in the chaotic landscape of education. Teachers love them because they sound like differentiation. Students love them because they provide an excuse: “I failed algebra because you didn’t teach it kinesthetically.” And publishers really love them because they can sell three versions of every textbook.

There’s also the allure of personalization. In an age where Netflix, Spotify, and DoorDash serve us highly tailored content, it’s comforting to think that education can too. “I learn best by interpretive dance,” says the hypothetical kinesthetic learner. “Ah, yes,” replies the teacher, “now plié your way through the Pythagorean theorem.”

The Real Issue: We All Learn Better with Multiple Modalities

Ironically, while “learning styles” are bunk, multi-modal learning—presenting information in more than one way—is supported by research. We all benefit from hearing, seeing, doing, and reflecting. A chemistry student probably needs to hear the explanation, see a diagram, perform a lab, and write a report to truly understand a concept. That’s not tailoring to a style; that’s just good teaching.

In truth, we don’t have learning styles—we have learning preferences, and those preferences are as fluid as a jazz solo. I may prefer to listen to podcasts on long drives, but that doesn’t mean I can’t understand a concept from a textbook or by watching a demonstration. And if you’re telling me I can only learn about mitochondria by bouncing on a trampoline (kinesthetic style), I regret to inform you: I’m not learning, I’m just tired.

Let's Retire the Sorting Hat

The idea of learning styles is attractive, but so is astrology. That doesn’t mean we should use it to build lesson plans. Instead of asking, “Are you a visual or auditory learner?” let’s ask, “How can I make this content meaningful, memorable, and accessible to all students?”

Let’s teach with variety, challenge with complexity, and engage with curiosity. And if someone insists they can only learn through color-coded charts and scented markers, that’s fine—but let’s not build an entire educational philosophy around it.

Because in the end, students don’t need labels. They need learning.

More References

Edutopia (2020). The Power of Multimodal Learning in 5 Charts.

https://www.edutopia.org/visual-essay/the-power-of-multimodal-learning-in-5-chartsUyanik, G. K., & Şentürk, B. (2020). The influence of multimodal learning strategies on prospective biology teachers’ literacy & numeracy.

https://www.ejmste.com/article/the-influence-of-multimodal-learning-strategies-on-prospective-biology-teachers-literacy-numeracy-15802Susilawati, S. (2021). The Effectiveness of Multimodal Approaches in Learning.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350365871_The_Effectiveness_Of_Multimodal_Approaches_In_LearningCenter for Curriculum Redesign. Multimodal Learning Through Media: What the Research Says.

https://curriculumredesign.org/wp-content/uploads/Multimodal_learning_through_media.pdfPaivio, A. Dual-Coding Theory.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dual-coding_theoryBahrick, L., & Lickliter, R. Intersensory Redundancy Hypothesis.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorraine_Bahrick