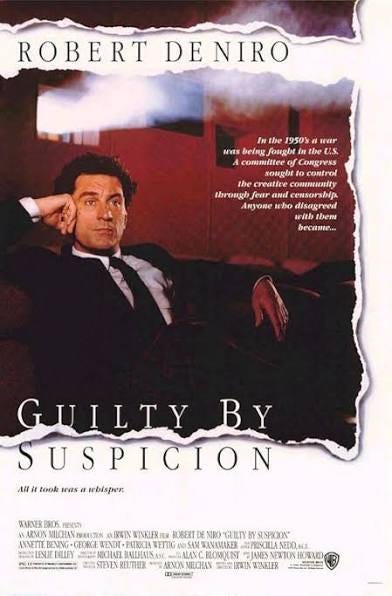

I first saw Guilty by Suspicion (1991) in theaters when I was in junior college, drawn by my admiration for Robert De Niro and my deep interest in the history of the Hollywood blacklist. At the time, I mistakenly thought the film was directed by Martin Scorsese—perhaps because of his frequent collaborations with De Niro or maybe because he has a small role in the film. Unfortunately, his acting skills left a lot to be desired, and his cameo felt more like a distraction than a meaningful addition. But beyond that minor gripe, the film left a profound impression on me.

What struck me then, and what resonates even more now, is how Guilty by Suspicion captures the creeping nature of political repression. De Niro plays David Merrill, a Hollywood director who finds himself blacklisted, not because he has done anything illegal, but because he refuses to "name names" before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). His downfall isn’t the result of any formal charges or evidence of wrongdoing—just an accusation, the whisper of suspicion, and the unspoken rule that those who don’t conform will be cast out.

Watching the film again recently, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was watching history repeat itself. In the last few weeks alone, we’ve seen two disturbing examples of guilt-by-association politics playing out in real time: the U.S. Department of Education’s new reporting system that encourages people to turn in teachers who discuss diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) concepts, and Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s attempt to strip Columbia University graduate student Mahmoud Khalil of his legal residency and deport him.

The Return of the Informant Culture

The Department of Education’s new "End DEI" portal is a chilling throwback to the surveillance culture of the McCarthy era. The program encourages parents, students, and educators to report instances where DEI concepts are being taught in public schools, framing these lessons as ideological indoctrination rather than discussions about race, history, and social justice. This is the same kind of environment that led to the blacklist—one where people were encouraged to police each other’s thoughts, to report on their neighbors and colleagues, to turn education into a battleground of ideological conformity.

This is exactly how HUAC operated: demanding that individuals prove their loyalty by reporting others, creating an atmosphere of fear that stifled free thought and open discussion. Teachers now face the same choice that blacklisted Hollywood artists did in the 1950s: self-censor or risk professional ruin.

Guilt by Association in the Rubio-Khalil Case

Meanwhile, Marco Rubio has been making the rounds on news programs, arguing that Mahmoud Khalil—a legal resident and Columbia graduate student—should be deported for his participation in pro-Palestinian demonstrations. To justify this extreme measure, Rubio has deliberately conflated Khalil’s activism with the recent occupation of Hamilton Hall, an event in which student protesters barricaded themselves inside a university building.

But here’s the problem: there is no credible evidence linking Khalil to the Hamilton Hall takeover. He was involved in earlier demonstrations, but he has not been accused of coercion, vandalism, or any action that would justify legal retaliation. Yet Rubio continues to blur these distinctions, painting Khalil as a radical threat and pushing to revoke his residency based on nothing more than ideological disagreement.

Much like HUAC, which destroyed careers without ever proving wrongdoing, Rubio is using guilt by association as a political weapon. He knows that by invoking “pro-Hamas” rhetoric, he can tap into public fear and justify extraordinary state intervention against Khalil—without ever having to present actual evidence of a crime.

How Guilty by Suspicion Warns Us About Today

What makes Guilty by Suspicion so powerful is that it doesn’t present Merrill as a radical. He isn’t trying to overthrow the government—he’s just a filmmaker who wants to work. But the political machine of his time demands more than silence from him; it demands compliance. He is expected to betray his colleagues, to prove his loyalty by feeding the blacklist. The film shows how institutions use fear to force individuals into submission—not just through direct punishment, but by making an example of those who refuse to conform.

That is exactly what’s happening now. The Department of Education’s tip line isn’t about protecting students; it’s about intimidating teachers. Rubio’s push to deport Khalil isn’t about national security; it’s about silencing dissent. Both cases show the same dangerous logic: if you challenge the dominant ideology, you are a threat. If you refuse to conform, you will be punished.

Are We Repeating History?

When I first watched Guilty by Suspicion, it felt like a historical drama—a reminder of a dark period that we had, hopefully, left behind. Watching it now, it feels like a warning.

McCarthyism didn’t just ruin the lives of artists, teachers, and activists; it eroded public trust in institutions and turned Americans against one another. It was a time when accusation alone was enough to destroy a person, when being associated with the "wrong" ideas could cost you everything. And now, in 2025, we are watching the same mechanisms of repression come back to life—just under different names.

The question isn’t whether we recognize these patterns. The question is whether we will stop them before it’s too late.