Rethinking Inclusion for Students with Disabilities

In Honor of Developmental Disabilities Awareness Month

I’m currently sitting in a breakout session at the All Titles Conference in Los Angeles, led by Nancy Hlibok Amann and Julie Rems-Smario from the California Department of Education, and Gina Ouellette from the California School for the Blind. This session has sparked a powerful discussion about what true inclusion means for students with disabilities—particularly those who are blind, deaf, or have other low-incidence disabilities.

The All Titles Conference is an annual event designed for education leaders, administrators, and program specialists working with federally funded education programs, including Title I (support for low-income students), Title II (professional development for educators), Title III (English learner programs), Title IV (student support and academic enrichment), and other state and federal initiatives. Hosted by experts in the field from the California Department of Education, the conference provides a platform for district leaders, school administrators, compliance officers, and education professionals to collaborate, share best practices, and gain insights into the latest policies, funding regulations, and innovative strategies for improving student outcomes.

March is Developmental Disabilities Awareness Month, a time to reflect on how our educational systems serve students with disabilities. While the Special Education Inclusion Movement is rooted in the idea that students with disabilities should learn alongside their non-disabled peers, today’s discussion raises an essential question: Is inclusion always the best approach?

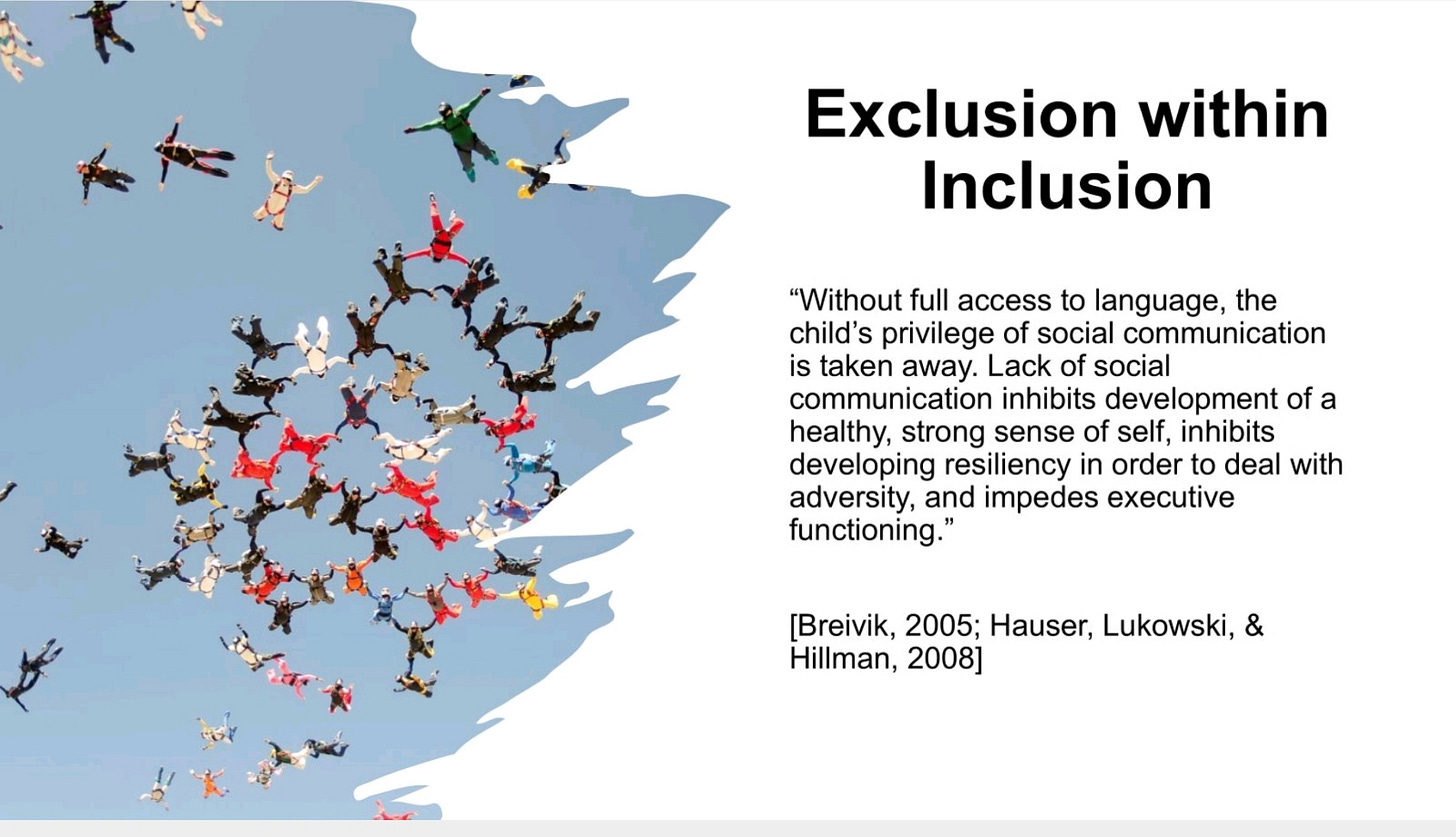

When Inclusion Falls Short

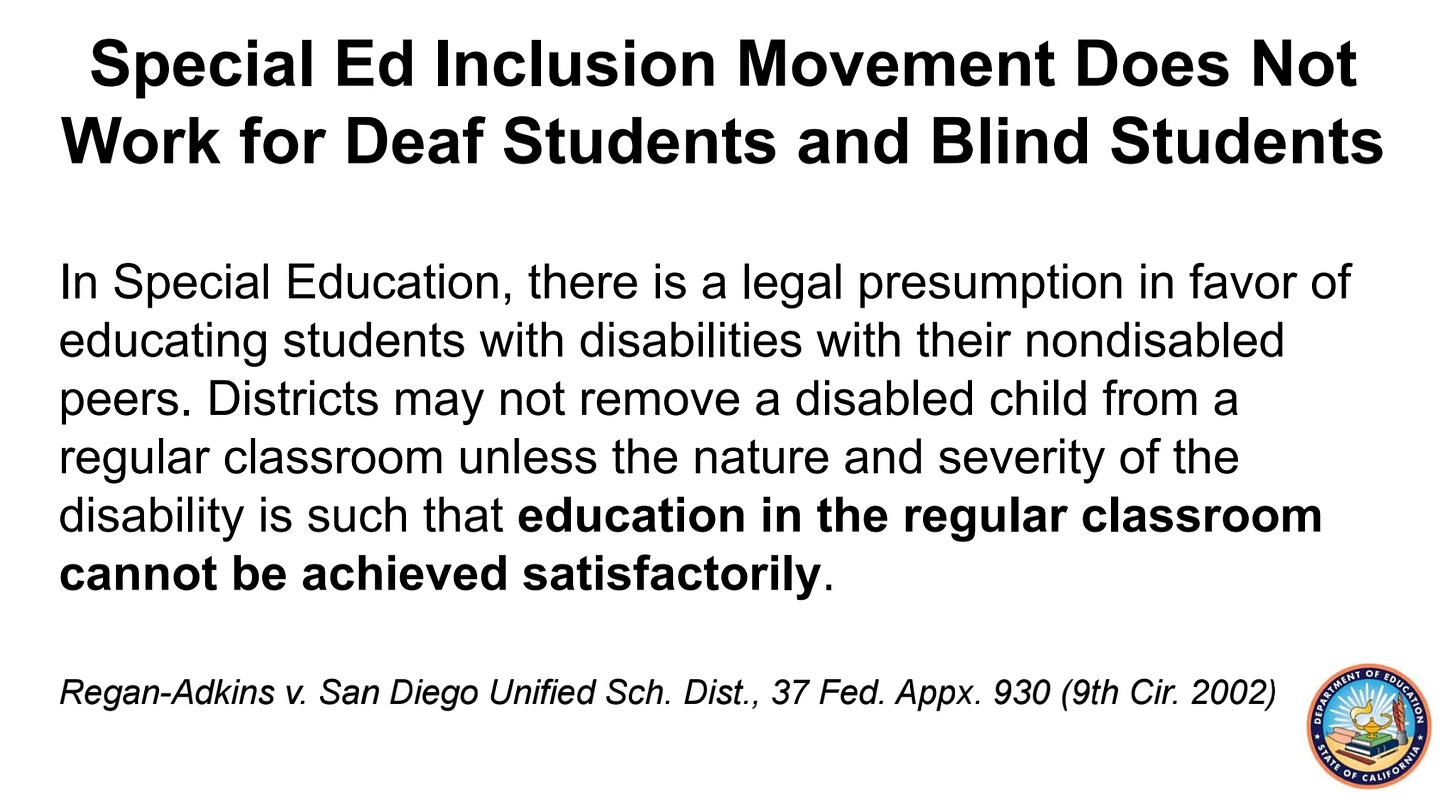

Federal and state laws, including the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), emphasize the importance of educating students with disabilities in the least restrictive environment. However, as the presenters at this session point out, inclusion should not mean forcing all students into the same educational model—especially when that model fails to provide the necessary support and access.

For students who are blind or visually impaired, a general education setting may not always be the most effective learning environment. The California School for the Blind (CSB) provides intensive, disability-specific educational services that local districts often cannot offer. CSB serves as a statewide resource for educators and families, providing expertise in:

Evidenced-based assessment and specialized curriculum

Assistive technology training

Braille instruction and literacy

Life skills coaching and independent living programs

Orientation and mobility training

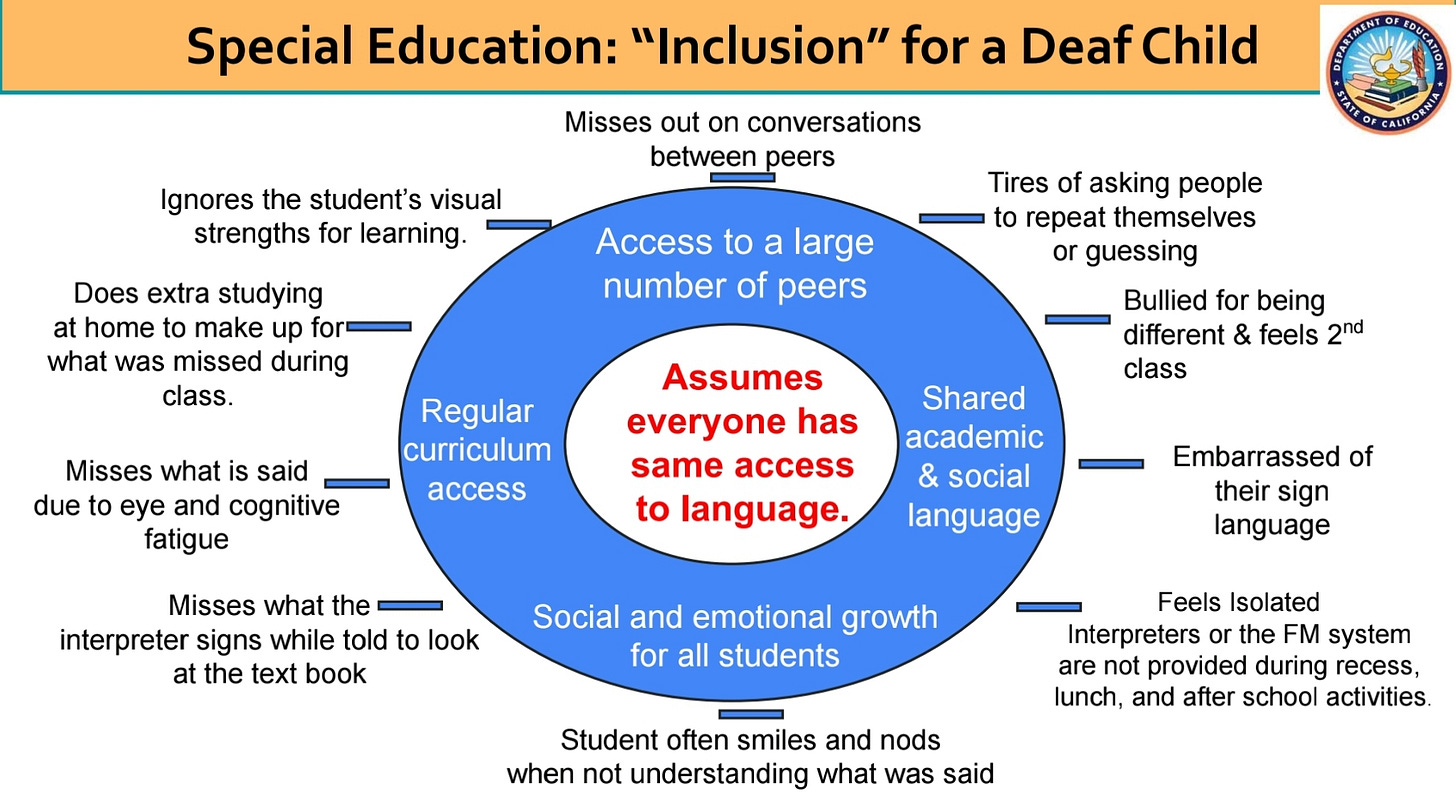

Similarly, for deaf and hard-of-hearing students, a general education setting often lacks full language access. Many deaf students placed in mainstream schools experience language deprivation, relying on interpreters rather than receiving direct instruction in American Sign Language (ASL) and English. According to the Deaf Child’s Bill of Rights (AB 1836), deaf students must have access to language-rich environments where they can interact with peers and educators who share their language.

One of the key takeaways from today’s session is that forcing students into mainstream classrooms without sufficient supports can lead to social isolation, academic delays, and a lack of access to critical resources.

The Power of Affinity Spaces

Another powerful discussion point from this session is the role of affinity spaces in education. Many schools provide student organizations focused on race, ethnicity, religion, and LGBTQ+ identity, yet disability-focused affinity groups are often missing.

The presenters introduced the concept of Blind and Deaf Community Cultural Wealth, which highlights how students benefit from being surrounded by peers who share their lived experiences. Drawing from Yosso’s Cultural Wealth Model (2005), this framework emphasizes six key areas:

1. Aspirational Capital – The ability to maintain hopes and dreams despite societal barriers.

2. Linguistic Capital – The intellectual and social skills gained through diverse modes of communication, such as Braille, ASL, and assistive technology.

3. Familial Capital – The cultural knowledge and support systems developed within disability communities, providing a counter-narrative to deficit perspectives.

4. Social Capital – Networks that provide practical and emotional support for navigating dominant institutions.

5. Navigational Capital – The skills to maneuver through educational and professional spaces not designed for disabled individuals.

6. Resistance Capital – Advocacy skills developed through challenging inaccessibility and systemic barriers.

This perspective challenges the common assumption that students with disabilities should always be placed in mainstream environments. Instead, for many students, being in specialized programs or schools is the most inclusive experience because it fosters identity, belonging, and access to a strong support network.

What True Inclusion Looks Like

A key takeaway from this session is that true inclusion is about access, not just placement. We must redefine inclusion to ensure that students with disabilities receive:

Language-Rich Environments: Deaf students need direct instruction in ASL and English, not just interpreters.

Expanded Core Curriculum (ECC): Blind students need specialized instruction in mobility, technology, and daily living skills.

Equitable Assessments: Many standardized tests fail to account for different communication modes, disadvantaging students.

Peer Access & Role Models: Students need teachers, mentors, and classmates who share their experiences.

The California Department of Education’s State Special Schools and Services Division (SSSSD) plays a crucial role in ensuring that students with disabilities receive the services they need. Schools like CSB and the California School for the Deaf (CSD) provide comprehensive programs that go beyond standard accommodations, offering students a holistic educational experience tailored to their needs.

As we recognize Developmental Disabilities Awareness Month, let’s challenge ourselves to move beyond compliance and toward true equity. How can we design systems that empower all students, rather than forcing them to adapt to structures that weren’t built for them?

It’s clear from today’s All Titles Conference session that disability inclusion must be about more than just physical integration—it must be about meaningful access to learning, communication, and community.

#AllTitlesConference #DevelopmentalDisabilitiesAwarenessMonth #Inclusion #EquityInEducation #SpecialEducation #DisabilityRights