Remembering ‘If’

Farce, Adolescence, and the Wisdom of Rudyard Kipling

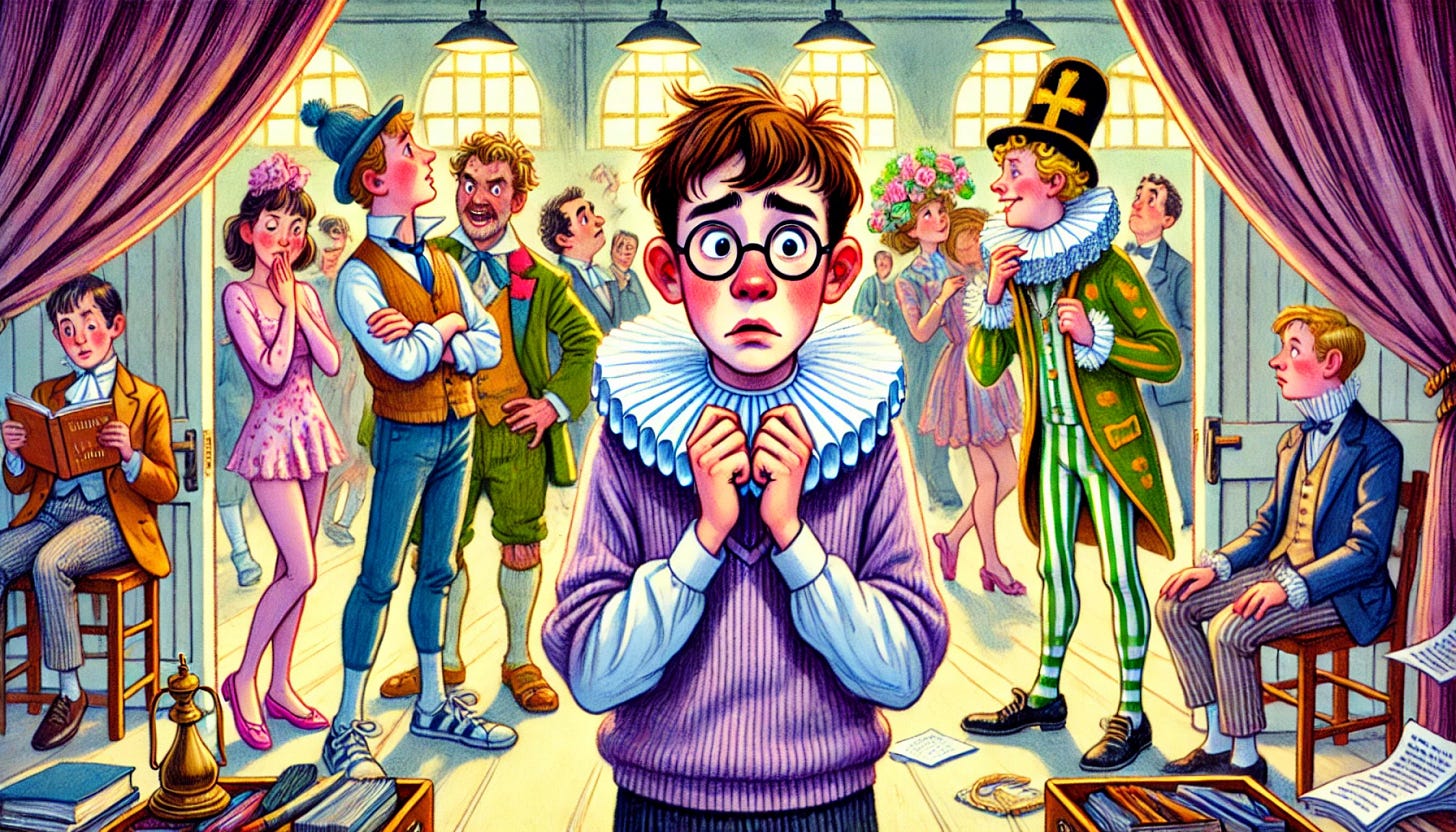

When I was a freshman in high school, I was cast in the senior production— See How They Run, a British farce so outrageously absurd it could have been written by Monty Python. The play, penned by Philip King, is set in the quaint English village of Merton-cum-Middlewick—yes, that’s the actual name, which sounds like it was generated by an AI programmed on a strict diet of Dickens novels. It’s a madcap whirlwind of mistaken identities, slamming doors, and enough vicars running around to staff a cathedral.

And who did I play? Reverend Lionel Toop, the local vicar. Reverend Toop is a well-meaning, slightly befuddled man who tries his best to maintain order, which is a bit like trying to keep a cat on a leash. He’s utterly devoted to his wife, Penelope, an ex-actress with a flair for the dramatic and a remarkable talent for inviting trouble.

The chaos kicks off when Penelope’s old friend, Corporal Clive Winton, shows up for a visit. For reasons that are entirely logical in farce but nowhere else, Clive ends up borrowing Lionel’s clerical garb to dodge military restrictions. This leads to a cascade of confusion with people mistaking Clive for Lionel, Lionel for Clive, and an escaped German POW for… well, just about everybody. At one point, there were more vicars running in and out of doors than in an Anglican relay race.

Right in the middle of this frenzy is Reverend Lionel Toop, trying desperately to keep his head while everyone around him is losing theirs—literally, in the case of identity, and nearly so with sanity. And here’s the kicker: as written by Philip King, Lionel actually recites stanzas from Rudyard Kipling’s If— throughout the play. Yes, it’s canon. Lionel, in all his bewildered glory, clings to Kipling’s wisdom like a life raft in a sea of absurdity.

And so, as the curtains went up on my high school’s production, there I was, a stocky fourteen-year-old vicar earnestly reciting, “If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs…” Little did I know how painfully relevant that would be for my teenage years.

At first, I memorized If— because it was in the script, and getting lines wrong meant facing the wrath of our over-caffeinated director. But as rehearsals wore on, I started to appreciate the poem. Its rhythm, its cadence, its message about resilience and integrity—it stuck with me, echoing in my head long after I hung up my dog collar.

The more I repeated the lines, the more they became a mantra. “If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster and treat those two impostors just the same…” They were words I held onto, especially when facing the many disasters of adolescence: failed math tests, unrequited crushes, and one particularly humiliating experience involving gym class and an ill-timed voice crack.

But back to See How They Run. In the middle of all the slapstick chaos, Lionel would take a moment, look out into the distance, and recite If—. It was absurdly poignant—like Hamlet’s soliloquy if Hamlet had been running from an escaped POW in a cassock. The audience would laugh, and I’d like to think they were laughing with Lionel, not at him, as he tried to find meaning amidst the madness.

Years later, I stumbled across a recitation of If— by Michael Caine. His voice—deep, gravelly, with just a hint of Cockney swagger—transformed the poem into something epic, almost Shakespearean. It was as if he was performing it for the Royal Shakespeare Company rather than a YouTube audience.

Hearing those lines again, I was transported back to that stage: the scratchy cassock, the wobbly set pieces, and the exhilarating thrill of delivering a punchline that actually landed. I could almost smell the combination of hairspray and nervous sweat that permeated the backstage area. I remembered being that earnest young vicar, desperately trying to hold onto some semblance of wisdom amidst the most glorious nonsense I’d ever been a part of.

I realized then that If— had stayed with me all those years, guiding me through the farce of adulthood as much as it had through the farce on stage. It had taught me how to keep my head amidst chaos, how to laugh at absurdity, and how to embrace the ridiculousness of life—even when life felt like it was scripted by Philip King himself.

Looking back, I’m grateful for that role and for Kipling’s words. Reverend Lionel Toop, bless his confused little heart, wasn’t just a character I played. He was a reflection of my younger self—earnest, bewildered, and navigating a world that made about as much sense as three vicars in a single vicarage.

I’ll always carry Lionel with me, just as I’ll carry If. Because sometimes life really is just a series of slammed doors, mistaken identities, and farcical misunderstandings. And when that happens, you just have to smile, recite a bit of Kipling, and keep running—just like Lionel Toop, and just like that wide-eyed kid on a high school stage.