Exiled by Faith

How Religion Changed the Course of My Life

When a friend recently asked me why I identify as an antitheist—why I harbor such a problem with religion, the concept of the divine, and even intangible ideas like beauty—I found myself reflecting on a memory that has quietly but profoundly shaped my worldview. I told them about the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran, a political upheaval that irrevocably altered the course of my family’s life. At the time, I was too young to grasp its magnitude fully, but as the years passed, it became increasingly clear how deeply the intertwining of politics and religion had affected me. The revolution was not just a historical event; it was a lived experience of displacement, disconnection, and, ultimately, a realization of the profound dangers posed by those who claim to speak for God.

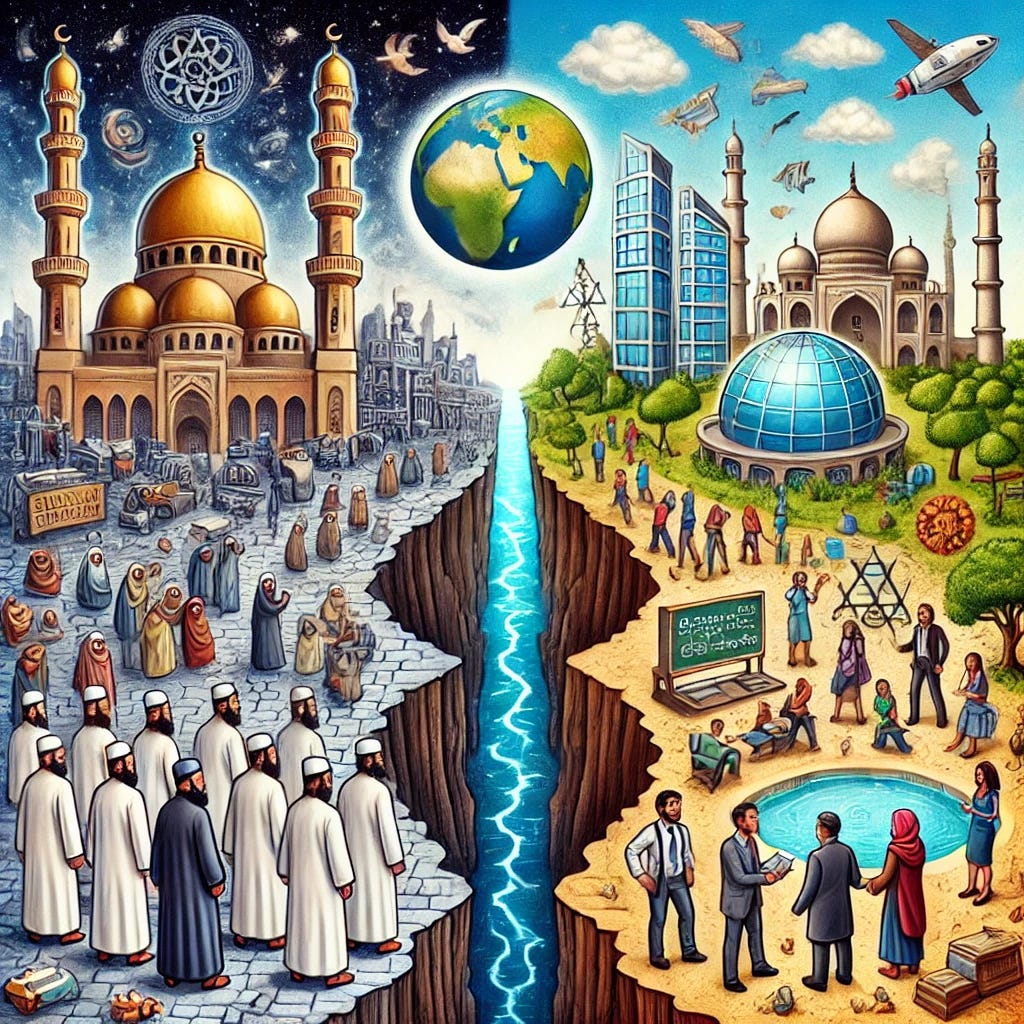

The Islamic Revolution marked the end of a secular monarchy and the beginning of a theocratic regime that fundamentally reshaped Iranian society. My family, like so many others, found ourselves at odds with the new order. The promises of a righteous society underpinned by divine will quickly dissolved into repression, war, and loss. What stands out most to me now is the role that faith—organized, militant, and politicized—played in justifying this seismic shift. People who believed they knew the will of God were willing to uproot entire communities, silence dissent, and wage war against those who deviated from their narrow vision of truth.

At the time, I wasn’t consciously aware of how this upheaval was shaping my mind. I knew only that my world had been upended. But as I grew older and began to process these experiences, I came to realize that my skepticism toward religion was not merely intellectual—it was personal. I had seen firsthand how faith, wielded as a weapon, could destroy lives. I came to resent the idea of God not just as a metaphysical question but as a justification for oppression. Religion, I concluded, was not simply a matter of private belief but a public force with the potential to cause immense harm.

Yet, as much as this realization clarified my antitheist stance, it also led me to wrestle with uncomfortable questions. What if the alternative—a world free from religion, governed by reason and rationality—wasn’t necessarily better? I imagined a secular Iran untouched by theocratic rule, and yet, the rational part of me understood that such a world could still fall prey to other forms of dogma, tyranny, and injustice. The absence of religion does not automatically guarantee the presence of virtue. Secular ideologies can also inspire cruelty and intolerance, as history has often demonstrated.

In this reflection, I began to see the limits of my own thinking. My critique of religion—its claim to absolute truth, its tendency to divide and exclude—could just as easily apply to other human systems of belief. This realization doesn’t absolve religion of its faults, but it does complicate the picture. The problem, perhaps, lies not in religion itself but in the human tendency to seek certainty and impose it on others. Whether clothed in religious or secular garb, this impulse can be equally destructive.

Even so, my antitheism remains deeply tied to gratitude for the life I now lead. I live in a pluralistic society where I am free to question, criticize, and reject religion without fear of persecution. The mere fact that I can articulate these ideas openly is a privilege that billions around the world do not share. In expressing my antitheism, I am not only rejecting a worldview that has caused me pain but also celebrating the freedom to hold and voice that rejection. It is a freedom I will never take for granted.

In the end, my antitheism is not merely a rejection of religion; it is a commitment to the values that religion, at its worst, denies—reason, autonomy, and pluralism. It is a stance born from the wreckage of displacement and a life shaped by the collision of faith and power. And it is a stance that thrives in the soil of a society that values dissent, diversity, and dialogue. For that, I am profoundly grateful.