If the first article on auto-exorcism I wrote was about clearing the ghosts from the mind, then this one—let’s call it Vol. II—was about torching the entire haunted house, dancing in the ashes, and inviting 100 people to watch.

My name is Emil. And once upon a not-so-distant time, I was an MFA candidate at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. I spent three intense years studying the craft of performance, dramatic writing, theory, movement, design, and the mystical sorcery known as scheduling rehearsal space in Macgowan Hall.

During my final two years, I was even given the dubious honor of being an adjunct professor for the sophomore class—which basically meant I had just enough authority to assign grades, but not enough to get a parking pass that didn’t involve a mile-long uphill hike and a secret handshake with campus security.

But the real story—my real story—was the thesis project.

The culmination of nine months of research, caffeinated paranoia, and metaphysical spelunking into the deep chasms of mythology, altered states, and the age-old relationship between artists and the divine, yielded a performance piece entitled:

"Ribofunk."

Yes. Ribofunk. A portmanteau of ribonucleic acid—because what’s more existentially volatile than DNA—and funk, as in George Clinton, as in Rage Against the Machine, as in that indescribable human soul grime that can only be danced through. The premise? A one-man musical fever dream with choreography, sleight-of-hand, strobe lights, and (I’m not making this up) spinal surgery performed on stage.

The central character was John Jezmund, a time-traveling antihero who was relentlessly pursued by a dark entity he simply called “the dragon.” John didn’t know why it was after him. Only that it always had been. (Foreshadowing, anyone?)

He leapt—Quantum Leap-style—into different lives:

A great ape who discovers a psychedelic mushroom and, in a burst of divine inspiration (and gastrointestinal confusion), promptly invents proto-language and primal song. His first utterance? Somewhere between a mating call and a jazz riff—think prehistoric scat singing with emotional baggage.

A neurosurgeon convinced we were living in a simulation, who performs experimental surgery on himself in a desperate attempt to free his soul. I, of course, played this scene straight—as one does—complete with fake blood, spinal props, and surgical monologue choreography worthy of a David Cronenberg matinee.

A grizzled old man ranting in the basement of a Christian church, railing against Abrahamic religion even as he accepted shelter beneath its rafters. Because hypocrisy, like soup, is sometimes all you’ve got.

Throughout the 40-minute show, set entirely to the rage and rhythm of Rage Against the Machine’s debut album, the story twisted and folded back on itself, until the character of John was forced to confront the truth: he was no longer escaping into other people—he was trying to escape from himself.

And that, right there, was the auto-exorcism.

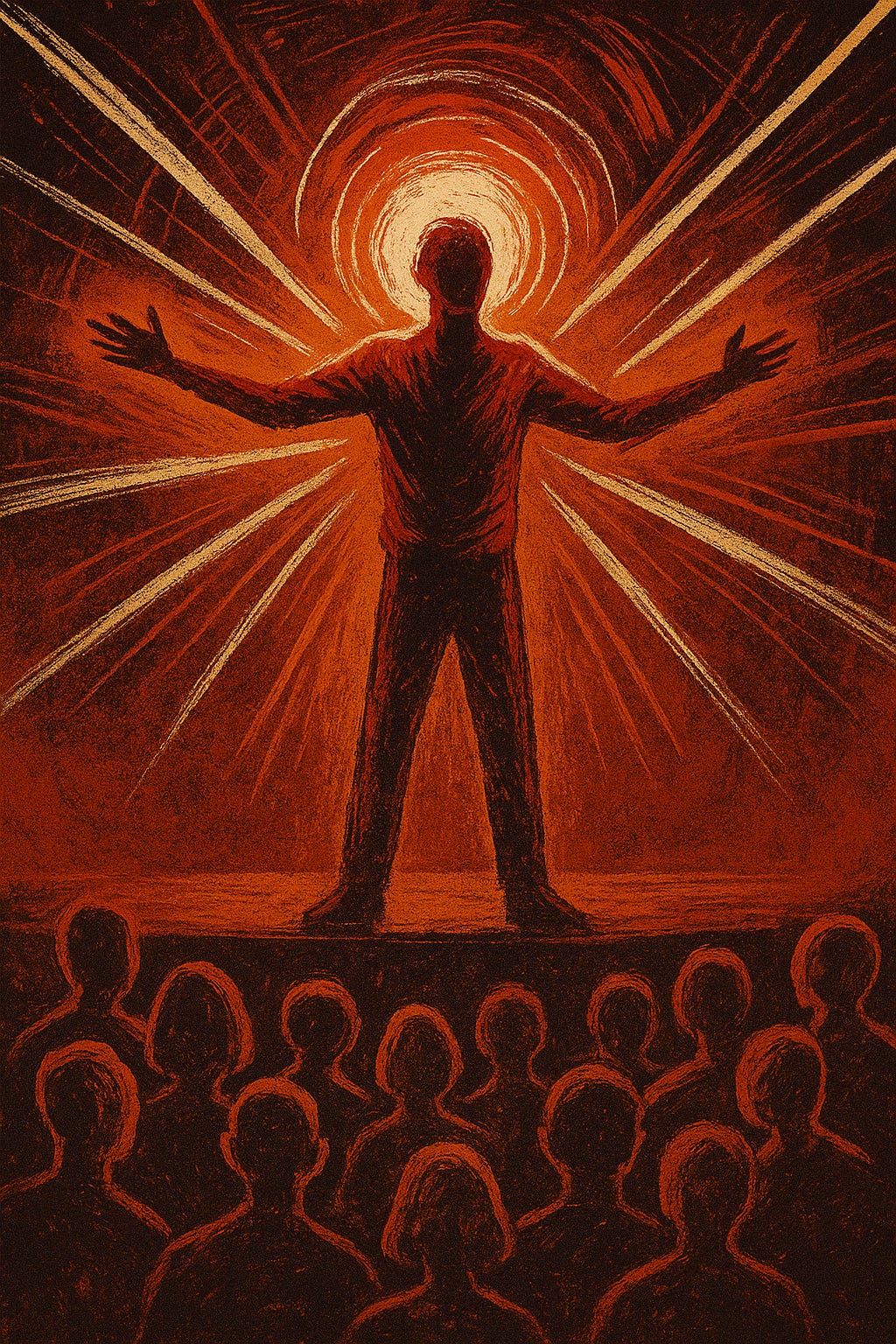

I stood on that stage, under the blistering white light, in front of my family, my beloved cousin Lara, my late girlfriend Sarah (may she rest in peace), and dozens of friends who probably expected a nice, digestible monologue about my artistic journey.

Instead, they witnessed a ritual.

At the end of the performance, John Jezmund dies. Or rather, he melts. He surrenders to the dragon. He stops running. And in that moment of annihilation, I stepped out of the role. Took off the costume. Stood, raw and real, as Emil—a man not yet finished with transformation, but done pretending he wasn’t being chased.

Because here’s the thing: the dragon never really leaves. It’s not meant to. It is the engine of the Great Work. The Hermetic path is not about escaping fear. It’s about refining it. About recognizing the heat of the dragon’s breath as the alchemical fire that purifies the self.

“Ribofunk” was my master’s thesis.

But more than that—it was my initiation.

It was auto-exorcism through art. An ancient rite dressed in stage lighting and distortion pedals. A reminder that we aren’t here to perform safety. We’re here to crack open our DNA and funkify the soul until we remember who we really are: fractals of divine intelligence, scared witless, singing anyway.

And I will never forget that night.

Not because it was perfect. But because, for once, I was.