There is a peculiar irony in the fate of an artist whose work is deemed too political for the very event designed to celebrate artistic expression. It’s like being disqualified from a chili cook-off for making your chili too spicy. Such is the case with Australian artist Khaled Sabsabi, who was recently removed from representing Australia at the 2026 Venice Biennale. His exclusion wasn’t due to a lack of artistic merit or innovation but rather because his work touched upon controversial figures—an act that, in the eyes of decision-makers, risked igniting public backlash. (And let’s face it, no one wants to deal with an angry X [Twitter] mob before their morning espresso.) The withdrawal of Sabsabi raises fundamental questions about the role of art in society: Is art a space for unrestricted dialogue, or must it bow to the pressures of public opinion and political sensitivities?

The Nature of the Controversy

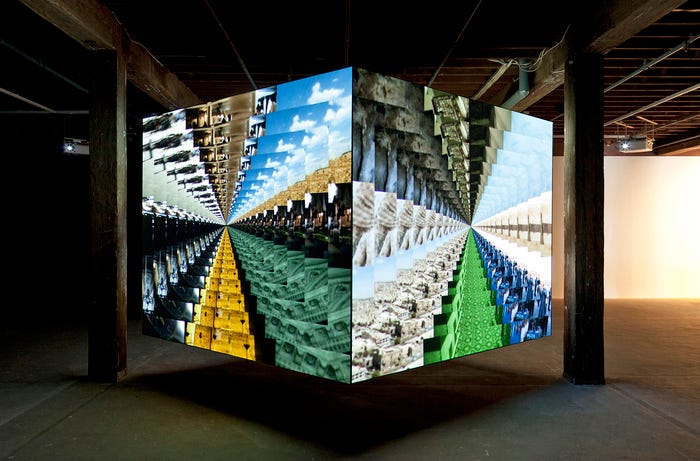

Sabsabi’s work has long been engaged with themes of identity, spirituality, and the geopolitics of West Asia. But apparently, his art was a little too spicy for Australia’s cultural palate. The concerns surrounding his selection stem from his past works that have depicted figures such as Hassan Nasrallah and Osama bin Laden—two individuals whose names alone can clear a dinner party faster than an unexpected political debate. It’s not uncommon for contemporary artists to explore complex subjects—indeed, art has historically served as a medium for confronting and questioning power structures, war, and ideology. However, Creative Australia, the organization responsible for Australia’s representation at the Biennale, determined that Sabsabi’s work could be too divisive for an international stage.

This decision begs the question: Does censorship begin when controversy is anticipated rather than encountered? If an artist’s work hasn’t even made it to the Biennale, what exactly is being avoided—genuine public debate or a really awkward press conference?

The Role of Art in Political Discourse

The intersection of art and politics is fraught with tension. While many advocate for art as an autonomous sphere, history tells a different story. From Picasso’s Guernica to Banksy’s latest cryptic wall graffiti, artists have repeatedly demonstrated that their work is more than just an excuse to wear black turtlenecks—it’s a form of political engagement. If art exists in a vacuum devoid of friction, then it ceases to be relevant. By preemptively removing Sabsabi, Creative Australia isn’t just silencing an artist; they’re depriving audiences of the opportunity to engage in difficult yet necessary conversations about war, extremism, and representation.

The irony, of course, is that this decision has now amplified the conversation that was meant to be avoided. Sabsabi’s exclusion has made headlines, turning his absence into a statement of its own. Had his work been displayed, perhaps it would have been met with critique, praise, or indifference—but it would have had the opportunity to exist on its own terms rather than as a bureaucratic ghost story.

The Precarious Line Between Sensitivity and Censorship

To be fair, institutions curating major international events must exercise discretion. After all, they don’t want the Biennale to devolve into a screaming match between online troll factions. The question is whether this discretion is being used to ensure thoughtful curation or sanitize challenging discussions before they occur. The Venice Biennale is no stranger to controversy; over the years, artists have used it to explore everything from colonial legacies to contemporary political strife. To say that an artist’s work must not risk division is to suggest that the Biennale is a place for comfort rather than confrontation—a notion that seems as out of place as a Monet painting in a punk rock exhibit.

Of course, there are always limits to what is deemed acceptable, and institutions can choose whom they represent. However, when those choices are based on fear of potential backlash rather than substantive engagement with the artist’s work, the result is a narrowing of discourse. The removal of Sabsabi is not just an isolated incident; it is part of a broader global trend in which cultural institutions, wary of controversy, err on the side of caution rather than courage.

Conclusion: A Disappearing Act as a Statement

Khaled Sabsabi’s withdrawal from the Venice Biennale is a reminder that the politics of art extend far beyond the canvas. In an age of rampant polarization and institutions becoming increasingly risk-averse, the actual cost of such decisions isn’t merely an artist losing a platform—it’s society losing another opportunity for critical engagement. Ironically, in an attempt to avoid controversy, Creative Australia created one. Whether or not Sabsabi’s work would have been provocative enough to warrant debate at the Biennale is now irrelevant. The real artwork, in this case, is the decision itself, and like all great pieces of art, it forces us to ask: What are we so afraid of? And more importantly, can we at least pretend we’re making these decisions for art's sake and not just because we’re scared of bad press?